To begin with, let me define the key term. Storage capacity refers to the capacity of energy being stored for a certain length of time until utilized (Gawel et al 2015). In Germany, storage systems only meets 1h of demand today (Gullberg et al, 2014). The implication of this to Germany's RE is that Since wind and solar power, which dominates Germany's installed capacity of RE, only produce electricity when wind blows or the sunlight is available, there is a significant gap in the amount of production during the day. When both are unavailable, electricity shortfalls can occur, causing massive destruction not only to domestic individual life but also to industrial activities. Germany used to consider nuclear power as a means of combating the shortages before the Fukushima disaster, yet, they decided to complete demolition of nuclear power plants by 2020, reflecting a strong public opinion against the supposedly dangerous, risky energy source (Gullberg et al, 2014).

Photo.1 Pumped-storage facility in Germany (Reference: Energy Transition, 2015)

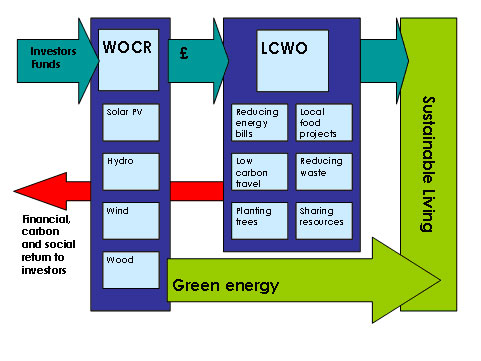

Technically, storage capacity can be increased using batteries, hydrogen, methane, compressed air and pumped-storage hydropower. However, these are generally inefficient and very expensive therefore not cost-effective (Gullberg et al, 2014). I think it is true that investing in these costly technology regionally would do nothing but leave a significant debt. Nevertheless, Germany recently embarks on a novel strategy that could resolve their problem, namely, international cooperation in electricity exchange with Norway (Gullberg et al, 2014).

Norway is known for its extensive installation capacity of hydroelectricity due to its geomorphology (Gullberg et al, 2014). In fact, the country's electricity sector is already almost completely dependent upon hydropower therefore produces almost no GHG emissions (Statkraft, 2015). Obviously, the country does not need to further develop RE considering the fact that they are fully functioned by hydropower. However, since there is still a great potential for Norway to expand the system, other European countries perceive the nation as 'green battery', meaning they are able to store energy produced by RE in hydropower (Gullberg et al, 2014). Basically, Norway pumps water from a lower elevation to a reservoir at a higher elevation using electricity produced from RE In Germany. Then, this low-carbon electricity can be stored and released to produce electricity to sell back to Germany when electricity prices are high in shortfalls (mostly at night) (Deutsche Welle, 2015). I think this is a win-win solution both to Germany and Norway - the former for solving intermittency problems, and the latter for making money and compensating for its fossil-intensive sectors - transport and heating. This helps achieve Norway's commitment to increase its share of renewables in the 'energy' mix to 67.5% by 2020 (Note that it's not 'electricity').

Photo.2 Hydropower in Norway (Reference: Celsias, 2015)

Some critics say the cost of installing new facilities particularly international grid connection such as in the North Sea and the one connecting the North and the South is extremely high. This challenge can be further complicated when environmental activists join in to campaign for nature conservation in the area of high-volatile cables being installed. The most recent example of opposition is those emerging to the building of a pumped-storage hydro facility at Atdorf in Baden-Wuttemburg (Gullberg et al, 2014). Furthermore, some Norwegian disagree with the proposal because they fear that development of new grid systems will increase electricity prices and that the use of land and water for pumped-storage will potentially destruct natural environments. The former is very true because energy facility is public owned therefore any cost associated with the development / maintenance will be reflected upon electricity bills (Gullberg et al, 2014).

Nevertheless, I suppose that Germany needs to go ahead with the project simply because they have no other choices. All nuclear power plants are now due to be demolished by 2020, and the dirty fossil fuel, lignite, naturally rich in Germany, has attracted a massive public opposition concerning deforestation, pollution and climate change. Some may argue that installing further RE in Germany would help reduce the risk of electricity shortfalls. However, I believe that regional / international cooperation is more important than achieving national energy security by generating renewable energy by 100% because the latter is very vulnerable to regional climate. For example, if anomalous rainy weather continues across Germany even for a couple of days, it will certainly lead to electricity shortfalls in many parts of the region particularly where storage capacity is low. By contrast, if places are connected to each other energywise, regionally, nationally and internationally, this can reduce the possibility of sudden blackout because they can exchange energy whenever necessary.

What I think Germany needs to develop the above system, primarily with Norway, is the following. First, political commitment of both countries is essential in order to attract sufficient investment to develop new infrastructure such as the grid system. As discussed in the earlier posts, the state involvement plays a fundamental role in increasing the investor's confidence therefore ensuring financial backing. Secondly, public debate over the development of the technology is essential to reach an agreement that minimizes the socio-economic and environmental costs of the project. As Gawel et al (2015) perceive the Energiewende as 'a long-term process of transforming a complex sociotechnical system', energy transition needs to come with restructuring societal systems including the change of people's perspectives and behaviours. Thirdly, the distribution of the burden incurred by energy transition should be taken into consideration more seriously. Gawel et al (2015) argue that It sometimes may not be intransparent or in contradiction to the fundamental values of fairness. Indeed, some consider the additional cost incurred by installing RE under the FIT system as a implicit environmental taxation that does not differentiate between the rich and poor. Clearly, it depends on the scale of geography (regional, national and international), yet there need to be some serious discussions over equity at high political level.

To sum, Germany's energy transition in the next few decades need to put more focus on how they cooperate with other countries like Norway to derive a win-win energy strategy. In this way, each country both maximizes and benefits from their potential economically. Some economists may consider this as an example of semi-competitive market, which represents the situation where a fairly large number of companies compete with each other in the industry with slightly different products. In other words, countries produce energy using different technology which is the most appropriate there both technologically and economically and trade it in the international market. Despite electricity transmission causes energy loss over a long distance, I think electricity exchange is still a viable option within a certain geographical proximity. Any thoughts or questions will be much appreciated!