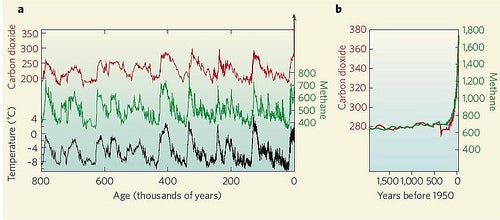

Figure.1. A left graph shows historical levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide (ppm), methane (ppb) and temperature (℃) over the last 800,000 years; A right graph consists of CO2 (ppm) and methane (ppb) over the last two millenniums. (Reference: Macmillan Publishers Ltd (2008) "Windows on the greenhouse" by Ed Brook, Nature 453: 291-292, in Environmental Defence Fund)

Similarly, there have also been anomalous rises in ocean surface temperature across the globe. This is attributed to the fact that ocean can absorb most of energy that enters into the Earth's climate system. In fact, 90% of all the energy has been stored into the ocean since 1971 (Light, 2014). Warmer ocean expands to raise sea levels that can cause economic and environmental destruction to coastal regions and islands, and trigger extreme weather through a greater amount of evaporation. However, what lacks in the analysis, I think, is that it is unable to draw a full picture of the potential effect of so-called 'still-inactive stored energy' in the ocean to the climate system in the future. What I specifically mean is that we cannot be sure whether the relationship between ocean temperature and the climate are in linear or logarithmic relationship, and therefore, whether the current rate of increasing and intensifying extreme weather would change in scale as more energy gets trapped in the ocean over time.

It is very simple - science cannot prove their prediction is 100% right nor wrong because of a number of limitations associated with their assumptions and methods. It is like sailing in the middle of the ocean where you only have a compass to guide yourself without a map. You know which direction you are heading to but never know if it is a right way to the destination you are aiming to reach. All you can do is to deduct from any signs like small islands, flow of the ocean, movement of fishes or birds to re-direct yourself to where you now think is an appropriate / better direction. Likewise, science is all about a sequence of observation and experiments that can or cannot provide you with a better prediction or solution. In the end, you have to make your own decision in whether to accept or decline the outcome.

Such uncertain and sometimes ambiguous elements of science have lost people's trust to some extent. Well, this is perhaps also blamed on to our tendency to over-trust scientists in providing a clear, definite answer to our question. However, in the context of global climate change, it might not be the case. What has been more problematic in our understanding about climate change over the last few decades, I suppose, is that many of us have failed to conceptualize it into something that is happening to our individual life, as 'our struggle'.

This is essentially due to the fact that spatial and temporal variation in the effect of climate change is very significant. Although temperature rises are expected in most parts of the world, the implication of the change in human's life is heterogeneous across the world (Thornton, et al., 2007). Their study suggests that whereas crop yields in Africa are expected to fall by 10-20% on average in response to future climate change, some regions are subject to increase. It is primarily because of topological variation in Africa, which plays an essential role in creating distinct rainfall patterns across the continent. For example, yields for maize generally increase at high altitudes while those at lower land see a drop due to increasing water stress when temperature rises. It is known as a temperature-driven increase in crop yields, with all other factors being equal (Thornton, et al., 2007).

Similarly, extreme weather is more intense in tropical regions because they absorb most of energy from the Sun and therefore temperature rises are the most significant. According to some numerical models, it is demonstrated that whereas global atmospheric temperature will go up to 4℃ by 2080 at the current rates of GHGs increases, it can rise up to 7℃ in southern Africa and 8℃ in East Africa (Independent, 2006). The estimation is very high and nearly double the global average level. Given that their lower socio-economic status, they cannot be well adapted to anomalous climatic events. Thus, climate change will certainly 'add more burdens to those who are already poor and vulnerable' (IPCC, 2007).

On the other hand, economically more developed countries, like USA, UK, Canada, France and Germany have tended to be and will likely to be less affected by climate change compared to the above regions. The fact is that these nations have been economically strong enough to ensure water, food and energy security more easily to meet their basic needs for life and economic activities, regardless of their actual physical potential. They are also better equipped with technology such as irrigation schemes and flood controls, which can help mitigate the effect of rising temperature or extreme weather induced by climate change - truly technocentric viewpoint.

Therefore, despite some big steps have been made towards the global climate change negotiation recently, it is clear that their historical attitude of arrogance used to prevent their citizens from realizing climate change as their potential struggle. In other words, it is only a recent phenomenon that people started concerning over global climate change as something close to their personal life - concerns over geographically widespread outbreak of diseases due to warming; more frequent occurrence of torrential rain, typhoon or hurricane causing destruction of houses and loss of life; increased possibility to suffer skin cancer; crop failures, etc. Whatever personal experiences above and more, what is happening nowadays is that people are increasingly re-conceptualizing climate change as from something irrelevant into something that really affects their life. This, I think, is where community power is recognised and begins to develop.

With this in mind, I think that now it is time to talk about examples of community power. In the next post, I will review some historical examples of collective actions that took place in response to the growing awareness of global climate change. The biggest question I'm going to address in the upcoming weeks is whether community power is truly 'powerful' in a sense that can make a contribution to mitigating global climate change. Perhaps, too many ambiguous, buzzy words in political science. If you have any thoughts about power of community, personally or generally, please feel free to make a comment here. :) See you all soon!

Truly interesting blog post Satomi. I agree people are now more aware of climate change impacts than ever before. However my fear is do they use climate change as an excuse to blame any natural disasters or any measures not taken in advance to reduce climatic catastrophes (e.g. flooding) or do they actually do something to reduce these climate change impacts. Look forward to your next blog!

ReplyDeleteHi Maria! Thank you very much for your comment with some thoughts into my post. Yes, I think that's a really good point. Climate change is not only a single fact about the Earth, but also can it be purposely used by politicians to hinder some potential development that is necessary for the most vulnerable. I guess that's where community power should emerge and help reflect real needs from the bottom in their governmental policy.

DeleteYes I totally agree!

DeleteInteresting set of ideas presented. Remember that not all blogs need to be as detailed! There are quite a lot of papers on perceptions etc. Here's a good one by the climate guru James Hansen

ReplyDeletehttp://www.pnas.org/content/109/37/E2415.short

Hello Anson, thank you very much for your comment and recommending me the paper! I think climate change is, at least to most of non-scientists, more to do with our perspectives and how these can be changed/developed within ourselves 'as a group' - which is where community power plays a key role. Now that I can keep blogging more frequently. :) Thanks again!

Delete