The above short line of argument based on the previous post highlights the importance of regionally-derived adaptation to climate change. However, 'adaptation' itself does not seem, in the first instance, to make a direct contribution to mitigating global climate change in any way. Clearly, we need to decrease the atmospheric concentration of CO2 to tackle its root cause, potentially through applying some of the methods in the following approach that geoengineers have recently proposed - Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR). Although I will not explore this in detail here as it is beyond the scope of the purpose of this blog, I will highly recommend any of you interested in this topic to read the following introductory paper by Caldeira et al (2013). One of my peers also writes her blog on geoengineering here if you are keen to discuss.

Coming back to the point, whereas 'adaptation' such as flood-control and changing crop patterns is critical to prevent a detrimental effect on people particularly the vulnerable, a 'mitigation' approach to climate change, exemplified in CO2 reduction, cannot be ignored to ultimately achieve a less violent climate and therefore more sustainable future of the Earth. They are not mutually exclusive but fundamentally interplay with each other. Indeed, the recent IPCC reports have put an increasing emphasis on adopting a balanced combination of the two in order to achieve security for sustainable food production, economic activity and ecosystem functioning (IPCC, 2014).

Now, the question is - can community-led actions help mitigate the effects of climate change?

Well, if you assume a single community power to be a catalyst for directly affecting the global climate, the answer is clearly 'NO' because any single community action on its own is comparatively way smaller than it can have a discernible impact on the planetary-scale climatic system. However, it is not what is being asked here. In essence, it is more to do with whether such a bottom-up approach is 'necessary' to ultimately achieve our sustainable vision of the Earth.

In order to address the question, let's explore the following example. Low Carbon West Oxford (LCWO) is a community initiative charity group, which was set up following the three major flood events between 2001 and 2007. Since its launch in 2007, they have been working on a wide range of carbon reduction schemes such as introducing sustainable transport system, encouraging local food production and development in renewable energy. With the emergence of an Industrial and Provident society 'West Oxford Community Renewables (WOCR)' in 2009, the two are co-operating with each other towards the reduction in the community's CO2 emission by 80% by 2050. Some of their success stories in 2009/10 include a cut of 140 tonnes of CO2 emission in 36 participating households through the Low Carbon Living Programme within one year, and 80 tonnes of CO2 through the introduction of 2 street cars shared by 170 people.

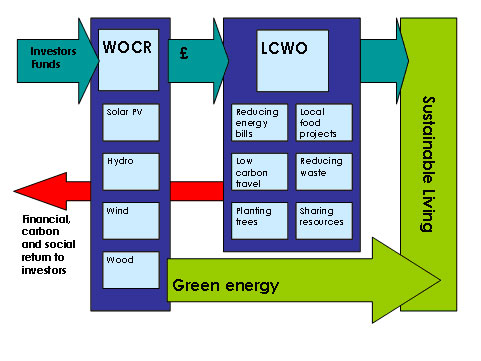

The key ingredients for their continuous success are the following; a) direct exposure to flood events that brought about serious concerns over the effects of climate change in their future generation; b) great leadership of the County and City Council; c) availability of grants and prizes helping boost community investment; d) model of re-investing locally created income through their programmes within the community such as into their further charitable work (Figure.1).

Figure.1. a diagram showing a flow-model of money and its contribution to sustainable living in the community of West Oxford. (Reference: Low Carbon West Oxford, 2015)

Barbara Hammond, a found of the LCWO, strongly supports the flowing model insisting that 'the economic benefit to developing these renewable energy projects is kept in the community, and can be used to create further economic development benefits about helping people to reduce their energy and therefore their energy bills', and thus, 'have a less pressured lifestyle economically' (Hammond, 2013). The first 5 minutes of the video below shows her summarizing their community work.

Again, the relative contribution of their community programmes to reduction in the global atmospheric CO2 concentration is very limited. Nonetheless, they illustrate the following two fundamental characteristics of community-led projects.

First, people are willing to take an action for their shared community concerns, not directly for climate change. Hammond clarified the point saying 'we all know you can't say that climate change caused that summer floods... but maybe this (experience of flood events) is the outcome of climate change. If I want my children to experience a different future, I need to do something about that'. In the research undertaken by Emergent Research & Consulting, (2012), such motive is defined as one of the two big factors that engage people in community action, so-called 'our future', meaning that sharing a story of a resilient and thriving place encourages their action.

Secondly, their community project essentially includes direct benefits to individual's personal life, for example, reduction in energy bills and transport costs. This is another motivation that the study pronounces known as 'here and now', calling for the immediate benefits of action to their personal life.

These two fundamental factors for success in community-led project are often overlooked in top-down approach of the central government, whose aims are, again, to achieve 'internationally negotiated CO2 reduction' in their country. They do not give much consideration to how climate change issues can be linked with and embedded into local concerns and struggles. That I think is where conflicts emerge between the central government and local communities because their local needs are frequently ignored under the national policy. Also, locally-funded nature of community projects is economically more sustainable than those under full financial support from the government because their central policy can easily be reversed or abandoned depending on their political situation.

Given that communities are the only geographical space where significant CO2 reduction can take place, it is anticipated that such friction would heavily undermine the ability of national government to practice their climate change mitigation policy in their land. Therefore, I think that a bottom-up approach to climate change is critical and should not be under-valued just because of their relatively small impact on the global atmospheric CO2 concentration. They are the best identifying some of the inter-links between climate change and local concerns and needs, which is fundamental to achieving a successful, long-term community action. Although the scale-up of community-led climate change actions across a wider geographical area will be necessary to reduce the atmospheric concentration of CO2 at global scale, the first priority in human-based climate change mitigation programs in any country should be given to empowering community to act 'for themselves and by themselves'.

I think this post highlights some of the essential roles that community power plays in tackling global climate change. Please do not hesitate to share your thoughts into this topic with me. :) P.S. Have a good reading week Geog folks!

Hi Satomi, before I say anything! What an honour mentioning my blog in your post. Thank you very very much! Your blog was truly intriguing.

ReplyDeleteYou mention that to reduce global CO2 levels is on empowering communities to act for themselves. I totally agree with this, however in relevance to geoengineering, do you believe this could be possible? I mean geoengineering is not greatly understood by many people, and is it the role of the people to decide whether geoengineering should take place? I believe, that people have the right to know and understand all geoengineering processes including the negatives and the positives. However, I am unsure to what extent they should be included in the decision making. Geoengineering is a process influencing many communities, hence who has a say in what decisions should be made?

I look forward to your next blog-posts and your answer :)

Hi Maria! Thank you very much for your comment again! Yes, that's a really good question. I personally feel that many of geoengineering approaches should be implemented at national or international level not at local level because it takes so long for everyone to approve it that would be too late to take a practical action. Of course, there're some local-scale measures that can easily be taken like brightening the roof mentioned in your recent post. but unless a certain geoengineering method has a potential to benefit 'the people', I believe it's hard to even discuss with them (except they are exceptionally eco-centric..). My apologies for this belated reply!

DeleteI totally agree with you Satomi! Even though an international approach may take a long time also due to many different opinions being addressed!

DeleteYes, that's a crucial point! In particular, when we successfully involve an individual or a group of people who are socio-economically influential within a community, it can lead to the prevalence of support across, which will potentially help develop the geoengineering scheme. So, if we want to include as many people as possible, we should first think of where to approach first.

Delete