Photo.1. showing wind farms outside the Feldheim village during a visitors tour.

Figure.1. A graph shows a shift in total emissions in some European countries from 1990 to 2012. Germany is one of the fastest, followed by the UK. (Source: National Geographic, 2015)

So, what distinguishes Germany from other European countries? Why have they been so successful in reducing GHGs emissions over the last few decades? These are some prominent questions I would like to address in the next few posts.

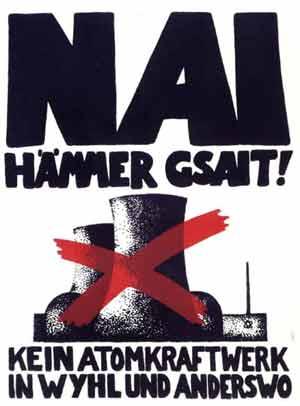

To begin with, it would be helpful to explore some historical backgrounds of energiewende. The origin of the term traces back to 1980 when the German Oeko Institute published a study called 'Energiewende', which signifies the possibility of economic growth with less energy, therefore nuclear and petroleum can be demolished and replaced by renewable sources (Oeko Institute, 2015). Prior to this publication was a historical movement against the construction of a nuclear power plant in Wyhl, the south-west Germany (Energy Transition, 2015). Near the location is Freiberg where residents were first politically pressured by the authority saying blackouts would be highly likely in the case the plant wouldn't start operating.

Despite the intimidation, local communities solidified to occupy the construction site and continuously demonstrated against their plan. In the end, the plan was abandoned - the first time ever the introduction of nuclear reactors was prevented in Germany (National Geographic, 2015). Now, Freiberg is known for its one of the highest per capita installed capacity in solar PV panels, with some 50 solar settlements which produce more energy than they consume (Rolf Disch, 2015). They are designed by a local architect Rolf Disch, who actively joined the Wyhl protests (Photo.2 & 3)

Photo.3. Wyhl protesters with a banner & placards (Reference: MITWELT, 2015)

In fact, a series of anti-nuclear movement in 70-80s was not simply because of their concerns over safety. It was also about geopolitical tension to which Germany was once forced to be exposed in forefront geographically, namely the US and the Soviet superpowers. The US used to (and still today) hold their nuclear bombs in West Germany against the former, and that was what agitated against nuclear demolition nationwide. It is still an ongoing debate in the country as the recent decision to increase the US's atomic weapons in Germany in spite of the 2009 parliamentary decision to gradually withdraw them - completely against the will of the citizens (Washington's Blog, 2015).

The following was the emergence of the Germany's Green Party advocating for pacifism and opposition to nuclear power plant (National Geographic, 2015). In 1983, first Green representatives won the election for the Bundestag, Germany's national parliament. It was one of the socio-political milestone in Germany that has constituted what the country looks like today. After the 1986's Chernobyl disaster, their influence has become inevitable.

In 1990 when Germany became reunified after the Soviet collapse, a first feed-in tariff (FIT) bill was passed through the Bundestag (Energy Transition, 2015). However, it was not until 2000 when the system started to fully exert a potential force. Hans-Josef Fell (Photo.4), who has been one of the most influential Green Party politician was a key person. He used to be a member of the City Council in Hammelburg before he joined the Party, and helped the council pass an ordinance that ensures the municipal utility to guarantee the payment to any renewable energy producers to more than cover the installation costs therefore make a profit (Energy Transition, 2015). 'The payment had to be so high that investors could make a profit. We live in a market economy, after all', he said (National Geographic, 2015). This market-oriented theory is marked by a number of studies (Nolden, 2013; Oteman et al, 2014) although the degree is highly dependent upon the nature of agency, institution and biophysical characteristics of countries (Oteman et al, 2014).

The success story of Hammelburg then led Fell to ride a Green wave and into the Bundestag where the Green formed a coalition with the Social Democrats (SPD). In 2000, he and Hermann Scheer (Photo.5), who is a prominent supporter for solar energy within the SPP, crafted a law called 'Renewable Energy Act' (Energy Transition, 2015). There are mainly two principles of the Act, first to mandate the FIT payment rates to be based upon the cost of investment instead of the retail rate (therefore above the market price), and second, to prioritize the renewable energy to be fed into a general grid with the guaranteed rate for 20 years.

Photo.5. Hermann Scheer (SPD) 'Faces of Energiewende'

This has made a number of individuals, communities confident enough to embark on their own renewable energy projects because they can plan well how long it would take to cover the cost and start making a profit. It also encourages active community investments on such projects because of the high creditability that the government provides under the formal legislation. It has been further accelerated by a traditional system of the state-owned bank KfW with €100 billion credit loans available between 2012 - 2017. These are some of the examples of structure-oriented force that explains the emergence of community initiatives (Oteman et al, 2014). As a result, there have been significant rises in many renewable energy production since 2000. For example, wind power generation almost doubled from 2000 and 2004 and still keeps growing until today (Figure.2).

Figure.2. A graph showing the shift in renewable energy production in Germany since 1990 in terawatt-hours.

Nevertheless, the country is not free of challenges. Firstly, since the 2011 Fukushima disaster, public opinion has been against nuclear power, which forced the government to call for a demolition plan of all their 17 plants by 2020 (Nolden, 2013). This raises a question about how the country would replace the supposedly 'green' energy, climate change-wise. Will they be successful in covering the nuclear generation by all the natural, clean force of energy? Or will they increase their import of nuclear / fossil fuel-based energy from nearby countries? There're also concerns about the over-exploitation of lignite (Photo.6), which is naturally rich in Germany, generating 26% of the total energy in the country (National Geographic, 2015). With hard coal mostly imported from outside (18%), the country still relies its energy source on coals by more than 40%. This also causes a massive destruction of Germany's beautiful forests through acid rain or mining activity itself.

Among these is traditional 'Big Four' (E.on, EnBW, RWE, Vattenfall), which have long been politically influential in delaying the energy transformation through lobbying (National Geographic, 2015). Today, they seem to rapidly increase the investment on renewable energy particularly offshore wind, yet, this could in turn price out small-scale community RE associations, which some critics say the another form of lobbying the government to favour big utilities in expanding RE. So, what would that mean to Germany's energy sector if community projects will not manage to increase in number and scale?

Among these is traditional 'Big Four' (E.on, EnBW, RWE, Vattenfall), which have long been politically influential in delaying the energy transformation through lobbying (National Geographic, 2015). Today, they seem to rapidly increase the investment on renewable energy particularly offshore wind, yet, this could in turn price out small-scale community RE associations, which some critics say the another form of lobbying the government to favour big utilities in expanding RE. So, what would that mean to Germany's energy sector if community projects will not manage to increase in number and scale?

From climate change perspectives, Germany also faces some other challenges regarding two major sources of GHGs emissions - transport (17% of GHGs) and heating system (30%) (National Geographic, 2015). The latter is to some extent locally provided by bio-gas through manure fermenter and direct heating from the sun (Oteman et al, 2014). However, the scale is very limited spatially and it cannot be expanded like a central energy system where electricity / gases are managed and provided by big utility companies. In addition, because of the biophysical characteristics of renewable energy, it's better to produce it where consumed. This is particularly critical when it comes to transmitting energy produced in the windy North to the more industrialized South where far more energy is demanded. The government and utility companies once proposed to build a high-voltage direct current (HVDC) such as the one connecting Bremen and Bavarian (Figure.3).

Photo.6. showing a mining site for lignite at Vattenfall

Figure.3. A map showing the HVDC networks that connect the North Germany and Bavaria (Source: National Geographic, 2015).

Nonetheless, controversies still remain high because some landowners have rejected it as unnatural disturbance spoiling the natural beauty in their land. Also, the transmission loss of energy (mainly through heat) could be another potential limitation that questions the effectiveness of such transfer projects. Therefore, I think that they need to further expand the existing local-based, decentralized energy system not only to achieve the Germany's ambitious GHGs emissions cut but also to ensure local energy security that helps improve the national energy security as a whole.

Here, I'm wondering how community energy production and big utility companies can cooperate, or compete well? Of course, what is the best way to provide energy to people is probably different from place to place, depending on the nature of agency, institution, and biophysical conditions as mentioned earlier. In the upcoming posts, I will try to address the questions raised above including the primary ones I mentioned at the beginning (perhaps one by one since there're too many). If you have any thoughts or questions, please feel free to share in comment. :)

how community energy production and big utility companies can cooperate, or compete well?

ReplyDelete→community energyにどうやって市場競争力を持たせる???

(読んだけど、誤読したり読み飛ばしてるかもしれない笑。もし文中に書いてあったらごめんね)

Hi Otaka san! My sincere apologies for being silent for a while. As far as I've researched on this topic, the ability of community energy companies to compete with large utility companies like Big Four is very much dependent upon both socio-cultural nature of the country and the degree of risk management community develops. In theory, if large utility companies provide cheaper energy with economies of scale than community power, the former wins the market. In the case of Germany, however, people choose to consume energy from the latter. This is attributed to the fact that their 'green values' discourage them to support the conventional fossil fuel-based companies. Even in the case they start to produce RE (which is actually happening nowadays), people are more inclined to support community energy because they're aware that the benefit of making local generation will flow back to that community. (Continue below)

DeleteNonetheless, it is also important to evaluate the risk management that community takes. I feel it is quite possible that small-scale community may, in the future, go under severe energy deficit and lose trust of the community if they don't establish a regional cooperation in energy exchange. Since RE production is very vulnerable to local biophysical nature (e.g. wind and sunlight energy), they need a kind of back-up plan. Large companies can do so by simply burning fossil fuel or make the use of an extensive geographical network of energy production across the nation, or even the world. This leaves customers no choice but a decision to rely on large utility companies. Perhaps, community energy is gradually forced to merge with them. I actually wrote about this in the next few posts if you're interested in. To sum, I think whether community can compete with large companies depend on how society perceives community energy and whether community undertakes sufficient levels of risk management. Do you, as a economist, have any ideas in this question? Or do you even think it is ideal for community to keep competing with large companies? I feel community engagement is vital in maintaining local production but I'm more skeptical of whether 'community management' is more appropriate than 'management by big companies'.

DeleteHi Satomi! A very interesting blog as usual! I agree with you that Germany has a lot of room for improvement, however I feel with government help they have done many changes. I was wondering how you believe developing countries may have the ability to advance their community energy productions since most of them do not have the economic ability? Also do you believe that Germany is a special case or that all countries have the ability to improve their community energy?

ReplyDeleteHi Maria! Thank you very much for your comment! Yes, I totally agree with you that government's intervention has been vital to Germany's Energiewende. Regarding your questions, I have once read an article stating that RE production actually causes more trouble than it benefits the society / environment. They argue that the energy security should not hinder other development objectives such as water supply, sanitation, education, etc. In fact, many of the rural populations in developing nations still rely on traditional energy source like fossil wood and biofuel, so, energy security is not in central debate in the country. Obviously some BRICKS like China and India have developed RE, they are mostly developed by the government for national energy security. I wonder whether it is even desirable for these countries to develop community RE. With regards to the second question, I think all other countries have ability to develop and improve community energy. However, it is highly dependent upon how energy politics evolves in the future. Also, it depends on the capacity of the pooling resources in community. These can be improved by social, educational programmes, yet, these indeed need sufficient levels of investment which are largely influenced by the government's future policy.

Delete